Today on the blog, I’m pleased to bring you an interview with the outspoken author and veteran, Renee James. Her dynamic and suspenseful writing not only keeps you turning pages, it brings Bobbi Logan, a refreshingly unique and gritty transgender character, to the stage. In writing Bobbi, Renee weaves some of her own experiences transitioning around complex and satisfying stories.

But is America ready to read a no-holds-barred transgender character? Although many people would answer yes, reading complex transgender characters can and does challenge our hidden biases. Readers are often conditioned to be comfortable with and understand the typical protagonist and even the stereotypical transgender character. In her open and revealing Bobbi Logan series, James smashes those expectations, grabbing readers by the collar, and dragging them into an entirely different and sometimes unsettling point of view. If you think you can handle it, read on.

DMS: In April, Sisters in Crime picked Seven Suspects, and specifically your protagonist Bobbi Logan as one of, “the most unusual detectives in mystery fiction.”

That’s a great compliment, especially from such a highly respected organization. And though some might think the distinction is solely because Bobbi is transgender, to me her most compelling and unusual aspects are that she is both brutally open and stunningly vulnerable. What do you think makes Bobbi a unique and compelling character?

“As an author, what I enjoy most is probing Bobbi’s constant questions about her authenticity as a woman.”

RJ: I wanted Bobbi to be the antithesis of media stereotypes of trans women at the time I began writing her (circa 2010)—smart, educated, independent, and witty. I also wanted her to be different than the trans community’s own stereotyping—not a victim or a survivor, but an achiever. Like everyone else on the planet, she gets mistreated, but she overcomes barriers with intelligence, grit and humor. Most of all, she refuses to let her gender identity define her. It’s part of who she is, but it’s just one of many components of her self-identity.

As an author, what I enjoy most is probing Bobbi’s constant questions about her authenticity as a woman. That gets us into what I consider profound explorations of how males and females differ, not in body parts, but in how they respond to pressure, confrontation, social interactions, conflict, flirtation—the nitty gritty of life. The gender stereotypes are mostly defined by our society, but no less profound for a transgender person to contemplate, especially one looking for role models. But some of the stereotypes are biological, too—our body chemistry dramatically affects things like muscle mass and emotional responses to positive and negative stimuli.

Where it gets really fun is, what happens when you spend, say, thirty years developing as a testosterone-powered human being, then change your chemistry to estrogen? For Bobbi, it’s part of the feminizing process, but there’s still thirty years of learned behavior to wrestle with.

DMS: I don’t think I’ll be giving away any spoilers by telling people your books are, as my tagline suggests, not for the faint of heart. They are searing and open, gripping and forceful. They make you feel and think. And amidst your thrill ride plots is an often vicious and biting sense of humor that serves as an incredible teaching tool. Is this something you did consciously, a way to draw the reader into character? Or is this something that comes naturally to you as a writer and communicator?

“Bobbi’s humor is a vital part of her intelligence and her courage.”

RJ: I can’t live in a world without humor, and I’d never ask a reader to spend hours with a story that didn’t have at least a few chuckles in it.

Bobbi’s humor is a vital part of her intelligence and her courage. She uses self-effacing humor to deal with her actual and self-perceived shortcomings. In today’s America, a lot of readers will blink at this—we’re supposed to be self-assured and self-satisfied, after all. But Bobbi’s self-effacing humor is its own kind of arrogance—she’s saying, yes, I have these flaws, but I don’t have to give a damn—if you do, it’s your problem. A lot of my transgender sisters who dealt with their gender issues in mid- or late life have this kind of attitude. It comes with being seen by others as a man in a dress. Their rebelliousness isn’t always expressed in humor, but they reach the same place: I refuse to let your perception of me be my problem—it’s yours.

I’ll confess, too, that the humor is part of my personal voice. It was a part of my family’s culture growing up, and, like Bobbi, I found it made life more fun in good times, and more tolerable in stressful times, like in Vietnam or divorce proceedings. I love that wry, ironic Russian humor that finds laughter in dire circumstances and I have tried to give that quality to Bobbi, too.

DMS: In your fantastic and riveting interview with Washington Independent Review of Books—everyone should read it––you used a word that often appears in your Bobbi Logan series when you said, “The motive behind all my Bobbi Logan books is to introduce the general population to a transsexual woman….”

Although transsexual is sometimes used to refer to a transgender person who has gender dysphoria and requires medical intervention (sexual reassignment surgery) so that their assigned gender matches the gender in their heads, this term can offend some and/or confuse others. Do you ever worry that using the word transsexual will confuse people about the relationship between gender and sexuality? Or offend others in the trans community who prefer the term not be used?

“Casting Bobbi as a transgender woman who had, indeed, gone through the medical interventions in gender transition was important to me, because that’s who I wanted to write about.”

RJ: To be honest, I can’t keep up with the evolution of acceptable terminology in the trans world. For example, when I first started writing Bobbi, it was still acceptable to use the word “transgendered”, but by the time my first book came out, “transgendered” was the social equivalent of an obscenity in the community.

When I was active in the trans community, “transgender” was used as an all-encompassing term, to include all people whose gender identity fell outside the traditional binary. “Transsexual” was a term used to describe people within the transgender community who were hard-wired in the “other” gender. This, in contrast to other transgender people who lived in both genders or between genders, or in some other state of gender non-conformity.

As it happens, several of my friends who self-identify as “transsexual” haven’t had surgery, and some others I’ve heard about don’t even engage in hormone therapy. It’s a state of mind.

Casting Bobbi as a transgender woman who had, indeed, gone through the medical interventions in gender transition was important to me, because that’s who I wanted to write about. Her life would be far different if she were, like me, someone who lived somewhat comfortably in both genders.

I certainly don’t wish to offend anyone with my terminology and I’ll certainly adapt if the community ever takes it upon itself to communicate its evolving vocabulary. That said, any glossary of terms that fails to account for the very broad spectrum of gender identities in our society is a failure.

DMS: I believe writing is one of the most vulnerable things a person can do. And for someone in your position, someone who doesn’t fit neatly into one gendered box, someone writing a transgender protagonist, someone well aware of the ravenous hostility of today’s climate, your courage stagers me. How did you find this bravery? Was it honed during your experiences as a soldier? Was it always inside you? Or is it something that can be taught or shared with younger LGBTQ+ people?

RJ: I think the lesson for young LGBTQ people—and probably everyone else—is getting to a point where you stop measuring yourself according to how others see you and start measuring yourself according to how well you are becoming the person you want to be. It’s not how you look, it’s who you are. Are you trustworthy? Do you try to lead a life of honor? Are you a good neighbor and a good friend? Do you have compassion and empathy? Are you developing your intellect? What are your moral and ethical beliefs? And, of course, so many other things that determine who we are, far beyond our physical appearance.

For me, this understanding began in military service during the Vietnam war. In those fractious times, I was doing something I didn’t want to do, something that was somewhat dangerous and extremely disruptive to my personal life, but I was fulfilling an obligation I had as a citizen and I did it with honor and without complaint. For this, I was despised by many members of my peer group–some looked upon soldiers as murderers, and others saw us as suckers. I was also shunned by many so-called “hawks” because they stereotyped young soldiers as drug addicts and losers.

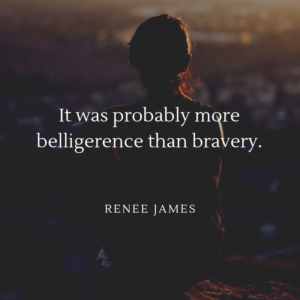

Going into bars and clubs back then wearing a GI haircut was a lot like going out into the general public in the 2000s as a visibly flawed transgender woman—people stared and avoided me, forming conclusions about me based solely on my appearance. So, that’s where it started with me. It was probably more belligerence than bravery.

As for being a trans author and writing about a transgender character, I don’t think that takes any special courage. You just have to be willing to be rejected by agents, editors and readers . . . and as you know very well Diana, every author in the world is in that exact same situation, regardless of their minority status.

All things considered, my reception as a trans author has been more positive than negative. One of the reviewers I solicited for my first Bobbi book was a self-described conservative Christian woman in the south. She took a chance on the book and even though she was uncomfortable with the book’s violence, she liked Bobbi and she gave Coming Out Can Be Murder a fair and perceptive review—and I should add, it was quite positive.

That’s how it’s been with readers and reviewers, for the most part. I get passed over by a lot of agents and editors for purely commercial reasons—there’s no ready market for transgender fiction to exploit, so there’s a lot of risk in publishing my books.

DMS: Living as a man, accepting that male privilege as you said, “is real and not just a societal bias,” how do you face your own biases enabling you to imbue books like A Kind of Justice with feminist viewpoints that are both authentic and relevant?

RJ: I hope my female characters are, as you say, authentic and relevant. That’s certainly what I strive for.

One thing about being a transgender person is, at some point, you begin to look at women as role models and mentors. This is like re-casting every female character in the story of your life. As a male, I understood women largely in how they related to men, socially, physically, emotionally, etc. As a transgender woman, I began to appreciate how women relate to their world, which is a different reality than the one men see because it’s based on different physical, social, biological and emotional truths than a male’s reality.

For me, it’s been a transition from sympathy to empathy, and the more I understand, the more profound my appreciation for femininity and feminism has become.

As for overcoming gender biases, because of the life I’ve led, I have a tendency to use violence in my stories. I’m trying to modify that—not to be more feminine, but to be a better story teller in a society that has way too much violence in it already. Ironically, one of my other challenges as a story teller is the desire to resolve conflicts way too soon, because it hurts to watch my characters in pain. Some might say that’s a feminine trait, but a lot of authors regardless of gender have the same problem. It takes discipline to make your characters’ conflicts work for you all the way through the book.

A sincere thank you to Renee for this candid and informative interview. It was an incredible pleasure to get to know her better. You can find out more about Renee and her series on her website, www.reneejames-author.com.

Renee James is a confessed English major and out transgender author who is also a spouse, parent, grandparent and Vietnam veteran. After a long career in magazines, James began writing fiction in 2012 and has published a series of novels profiling the life and times of a

Chicago transgender woman, Bobbi Logan. Most recently, she published her first short story, Two Nights with Suzie Wong (https://www.

Remarkable. Thanks for this.

Isn’t she remarkable? A fascinating woman. As are you, my darling friend.